Sometimes young people are left out of the conversation about what they need to succeed.

As policymakers and educators debate how to help high-schoolers from all backgrounds get to and through college, young people’s ideas about the support they need to succeed are sometimes left out of the discussion. Yet conversations with students who are the first in their families to pursue higher education reveal seemingly small things that, added up, can make the difference between dropping out and graduating.

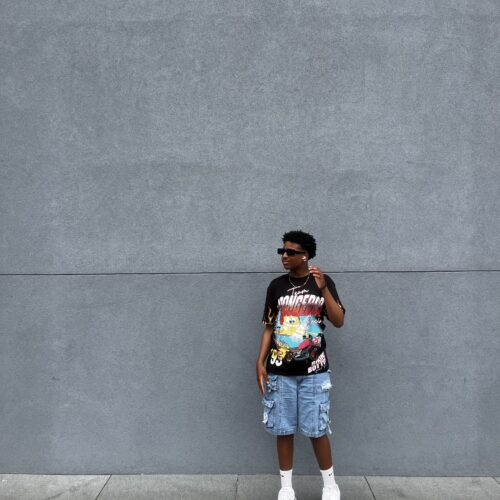

Greg Dendy was raised by a single mom in a southeast Washington, D.C., neighborhood he recently described to me as “pretty underserved.” Statistically, he is unlikely to graduate from college. According to the Pell Institute, only about 11 percent of low-income, first-generation college students earn a bachelor’s degree within six years. Yet Dendy is well on his way to collecting a diploma. He’s just finished up his sophomore year at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, where he’s a class officer and a member of a music fraternity. He’s already making plans for graduate school, and hopes to one day get a call from the president to serve as U.S. attorney general.

How’d he do it? And, more importantly, how can the U.S. help put more students like Dendy on a similar path? He’s got some ideas.

College “was always an expectation,” he said. His mother talked about it. His teachers talked about it. Everyone talked about it. The mentality that college is the logical step after high school—an idea that is baked into the upbringing of so many middle-class children whose parents have degrees of their own—was reinforced early and often as he grew up.

Dendy’s high school, part of the Knowledge is Power Program (KIPP) charter network, encouraged him to take advanced-placement classes and even a course at a local university, which gave him a taste of college life. They required him to enroll in a class about how to apply to colleges and then helped him research options. By that point, he’d also connected with a nonprofit called PeerForward, which works with high schools to help more students enroll in college.

One of Dendy’s favorite teachers had graduated from Fisk a few years earlier, which sparked his interest in the school. “I felt like she was a great person,” he said. “I was like, if I want to be great, I’ve got to go to the same school as her because what isn’t great that doesn’t come out of Fisk University?” His counselors and mentors could have left it there; they could’ve simply applauded the fact that he was applying to a four-year college at all. That happens far too often. Recent research has indicated that few high-achieving poor students apply to schools that match their ability levels. While students with parents who have navigated the college-application process are presented with a range of options, a kid with decent but not outstanding grades might apply to a local state school that admits nearly everyone, and Harvard, because he’s heard about both and isn’t aware of good options in the middle.

“My whole idea was I would go to Fisk and Fisk was the only place to go. I didn’t think about those safety and reach schools,” Dendy said. But his school and PeerForward mentors did. Initially Dendy was put off by the idea of expending energy by applying elsewhere. “I was like, okay, I see what you’re trying to do here,” he said. “You’re trying to pull me away from Fisk University.” It wasn’t until later that he understood that, “in actuality, they wanted to make sure I was safe.”

The application process was daunting, he said, but he persevered in part because his classmates were also going through the same struggle. “You think you’re doing this alone but there are actually people all over the world doing the same thing as you,” he said. Dendy ultimately received an acceptance letter from his first choice, and headed off to Nashville.

When Dendy, the oldest of four children, left, his brother and sisters, he said, “felt like there was going to be some void left in the house.” His mother worried about him being a 13-hour bus ride away. Dendy wondered if he’d made a bad decision. Arriving in Nashville did little to assuage his concern. “Is this a city?” he wondered. “It’s pretty slow. It’s nothing like D.C.” He was surprised when he tried to pick up something to drink at a local gas station one evening and found it closed. But his mentor from PeerForward called him frequently to check in and tell him he was “a leader,” he said, setting a precedent for his siblings.

Still, the first year was full of the unknown. Even packing to live in a dorm was complicated. “I had to pack everything not knowing what to actually take,” he said. Later he’d discover he only needed some of what he anticipated. And then there was the matter of roommates. “How am I going to live with another person in a dorm who I don’t know?” he worried. His family helped him move in but had to return to Washington immediately, while his roommate’s mother lingered for days. As the pair were preparing to attend a welcome ceremony, Dendy was shocked to see her ironing the young man’s shirt, something he’d long been doing for himself. Balancing a full course load with as many as 20 hours a week at a restaurant job off-campus also meant he did homework in short spurts during breaks, or late at night after closing, while his classmates socialized.

Plenty of universities leave it up to students to show up to class or not, to take advantage of office hours or not, to succeed or wash out without the help of college counseling. But his professors, he said, would text him a few minutes before class to make sure he was on his way. One teacher tracked him down at his job after he missed class to work. Another spelled out exactly how much money students were paying per class and how much money would be wasted if they slacked off and had to repeat it. Initially, he thought professor office hours were just something the university “threw in the air” to attract students. But then professors asked where he was. “It’s like, okay, you really do care about me,” he said. “It’s all about the support that you have.”

Besides support from professors and mentors back home, his mom called him daily in the beginning, and he developed a close group of friends through on-campus activities. Surrounded by a network, he now feels encouraged to take risks, like joining student government, that will likely pay off in the long run. “That’s all there is to it,” he said, “just being able to step out of your comfort zone.”

This article originally appeared on TheAtlantic.com, June 11, 2016